With limited space to build, Hong Kong has gained a reputation for having some of the smallest and most expensive apartments anywhere in the world.

For Max Lee, a 26-year-old Hong Kong doctor, life in his single-room apartment revolves around the bed. It’s the first thing you see walking in.

It’s where he not only sleeps and watches television, but also where he studies medical literature when not at the hospital — his laptop perched on a narrow work table at one end. Lee chose this 220 square foot space in a glassy high rise in the busy heart of Kowloon so that he could afford to be in the city center. “It’s alright to live here alone,” he says, “but when my girlfriend comes over, it’s very crowded.”

Lee’s home space might seem unusually small but the unit he lives in is in fact of an increasingly common type: the microflat. Hong Kong possesses around 8,500 of these tiny units, which represented 7% of all construction at their peak in 2019.

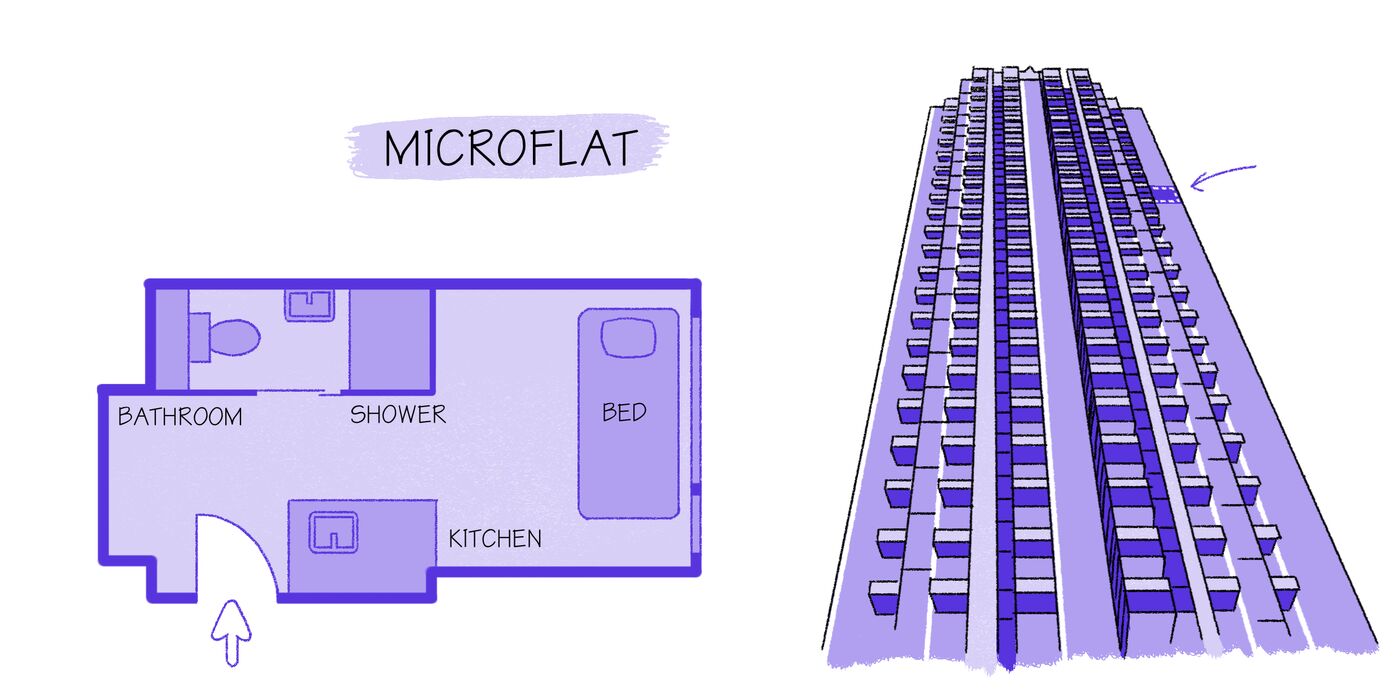

Look up at any sparkling new residential tower in Hong Kong, there are likely people crammed into flats like these. Far from the romanticized U.S. “tiny house movement,” these are single rooms about half the size of those spacious-by-comparison houses, with only enough space for a bed, cabinet, tiny bathroom and a kitchenette. They are marketed as “affordable homes.”

It’s Hong Kong’s status as one of the world’s most densely populated cities — and the least affordable — that fuels this market. A critical shortage of housing caused home prices to soar 187% from 2010 through 2019, according to government data. Now average home prices exceed $1.3 million in a city where the minimum wage is just $4.82 an hour. Even a skilled worker in Hong Kong must work 21 years to afford an average (650 square foot) apartment near the city center, the longest such period in the world, according to a 2019 report from UBS, and prices remain at near record highs despite the Covid-19 pandemic.

Microflats, costing half an average home’s price, offer access to the property ladder’s lowest rung. The tiniest of these spaces, at 128 square feet, known as nanoflats, are smaller than most cars and their parking spaces. Buildings such as “One Prestige,” built in 2018 in Hong Kong Island’s North Point neighborhood, cater to not just first-time homebuyers but also to pied-a-terre purchasers from mainland China and elsewhere. With units ranging from 163 to 288 square feet, some have current asking prices of $800,000 to $1 million ($3,900 to $5,300 per square foot).

Property developers have responded to the demand for more affordable housing by increasingly parsing floor plans into ever smaller units, a trend that took off in 2015 after the government loosened regulations requiring natural light and ventilation. Previously, fire-safety codes required kitchens to be set apart by a wall, with their own window, obliging developers to build interior windows into courtyards or air shafts to allow the separate kitchens to have light and air flow. The changed regulations allowed for open kitchens, lit by a single window at the unit’s opposite end. Developers began constructing narrow, side-by-side units facing a single hallway, with a kitchenette near the door.

The result is a kitchenette much like a hotel minibar, with the simple addition of an electric hotplate or burner. There may be a built-in microwave, but never an oven. And the bathroom may or may not have a shower stall; sometimes the showerhead is simply above the toilet.

The move toward smaller units nonetheless predates the regulation changes. It reflects Hong Kong’s unique geography and unusual history, as well as a system of loosely regulated capitalism inherited from its days as a British colony. Small-living was born of Hong Kong’s refugee mentality as a place where many thousands of people fled from China, and it got its start in crisis. In 1953, a fire on Christmas Day in the hills of Kowloon’s Shek Kip Mei neighborhood destroyed a shanty housing refugees from China, leaving more than 50,000 people homeless. Rather than distribute charity to the displaced, the government rapidly constructed resettlement estates to house them, initiating the city’s public housing program. The Bauhaus-style Mei Ho House allocated 120 square feet to each family. More than 300 people had to share six toilets. Even these crowded spaces were a step up from their destroyed hillside shacks.

“People did not really object or complain, because they did not have the grounds to complain,” says Ng Mee-kam, an urban studies scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “We have to imagine going back in time. There was a time, talking about the 1950s, when most Hong Kongers were refugees running from World War II, civil war, and then the Communist Party taking over in China. They had this refugee mentality. If you just escaped from a former place that you don’t desire to live in, then you would not have a lot of expectations in a new place, because your whole purpose would be just pure survival.”

That’s difficult to picture in the present day, Ng says. “Today we have all this vocabulary, international discourses about housing rights, housing affordability. We think this is basic human right to have a decent place to live. At that time, it was a totally different story,” she says.

Hong Kong’s topography also promotes the tendency toward small units. The mountainous landscape of its islands isn’t suitable for development, and 75% of the territory is green space or natural landscape, much of it in the form of protected country parks. That preservation effort was led by former Hong Kong governor and a keen outdoorsman, Lord MacLehose. As the city’s population swelled in the 1960s and ‘70s, he designated Hong Kong’s vast forested terrain for government-managed conservation. The resulting 24 country parks act as an important watershed for Hong Kong’s limited water supply, as well as preservation for 443 square kilometers of forests, grasslands, wetlands, rock formations, and more than 3,300 species of flora.

This means that the city is far more crowded than overall data suggests, as just 7% of land is zoned for housing. Its 7.5 million population must cram into dense, high-rise neighborhoods sandwiched between sea and mountains. The most crowded district is Kowloon, with a population density of 49,000 people per square kilometer, or nearly double the 27,600 that reside in the same amount of space in Manhattan.

Government policies favoring a handful of elite developers have worked to create this style of accommodation and its grudging acceptance among Hong Kong’s population. To own a room of one’s own, even one smaller than a parking space, can be considered an improvement on public housing — in which almost half the population lives (and for which there is a six-year waiting list) — and the even smaller “cage” or “coffin” homes: 100-square-foot stacked bed spaces rented to Hong Kong’s lowest-income residents.

Hong Kong’s capitalist, neoliberal mentality allows such cramped housing to persist, Chinese University’s Ng says. The thinking is “if you cannot afford to buy a decent home, it’s your own fault.” Those who can manage to get onto the property ladder then have an interest in supporting the status quo of keeping property values high, she says.

The social and psychological tolls for Hong Kong’s people, however, have mounted. The first study of its kind, published in July 2020, found a significant impact of housing size on high levels of stress and anxiety.

“I have talked to people who said they wanted to commit suicide as a result. I met a father who worked many hours a day to pay rent and was getting off work to a home so small that he wanted several times to jump off a building,” says Chan Siu-ming, the study’s lead author, now assistant professor of social and behavioral sciences at City University of Hong Kong. “They would feel depressed and hopeless. Small living space usually comes with less lighting or ventilation, so it feels oppressive if you live there for a long time. The common result is that you don’t want to stay home.”

That means much socializing in Hong Kong takes place out of doors. Hong Kong became famous for its open-air dai pai dongs, and its teahouses, where men traditionally gather for breakfast and a smoke, read the morning papers and chat about politics. On weekends, it seems all of Hong Kong is dressed in sporting gear, hitting recreation centers, public pools and beaches, tennis and basketball courts. Before Covid restrictions closed them temporarily, public barbeque areas hosted large group gatherings on weekends. Hiking groups swarm through the mountainous, sub-tropical forests of the country parks, where development has been zealously fought off by civic organizations and those who recognize that Hong Kong people live in this precariously balanced trade-off. Shopping malls, with their chilly air conditioning, also provide a spacious, weekend escape.

Yet living in small spaces also requires families to consider consumer purchases carefully. Hong Kong apartments don’t come with closets, meaning that wardrobe cabinets and other storage take precious square footage away from the living space. With the size of even a non-microflat averaging about 650 square feet, families have little room for belongings and must be judicious about what they purchase and how long they keep it. Among the well-heeled, last year’s fashions are quickly discarded for this year’s (though those with resources also use self-storage facilities to store clothes between seasons.)

Furniture — often mini as well as minimalist — must also be kept at a minimum. In a microflat, these choices are even more extreme. A promotional video for One Prestige shows how the single room transforms from leisure to dining to sleeping: A low coffee table in front of a small sofa rises to to become a dining table, and then at night the sofa folds out into a bed over top, taking up the whole area. The reality behind that magic would require expensive, custom-built furniture, of course. More typically, a small bed like the one in Dr. Lee’s flat hosts all of daily life’s functions: seating, dining, working and sleeping.

Yet unaffordable housing “is regarded by many as the ultimate cause of Hong Kong’s deep-seated social conflicts, including the wide wealth gap, ever-deepening economic concentration, and a disenfranchised majority of citizens who must struggle in a chronically high-cost, housing-deficient economic environment which offers dwindling business and job opportunities,” writes Alice Poon, author of “Land and the Ruling Class in Hong Kong,” which sold out eight printings in the six months after it was published in Chinese in 2010.

Poon, who had worked for a major property tycoon of the British colonial period, coined the term “real estate hegemony” [地產霸權] to describe how these developers wielded extraordinary influence over government policy. Buying up massive land banks, they then kept them undeveloped until rising prices due to lack of supply allowed them to boost profits at the expense of working people with little means to buy into the system.

To address concerns over the housing supply, Hong Kong’s government in October announced a plan to create a Northern Metropolis with housing for 2.5 million people near the border with China. China’s mainland leaders, who have increasingly tightened their control over the city, have blamed unaffordable housing for massive social unrest that erupted in 2019 and called for policy solutions. The completion of these units would be years away, while supply has continued to constrict. The number of private homes that can be produced from available land plots plunged from a peak of 25,500 in 2018 to 13,020 in 2021, according to think tank Our Hong Kong Foundation. Home values have risen a further 5% so far in 2021. City officials have also expressed a desire to stop developers from building the tiniest of homes, of less than 200 square feet.

Markets can sometimes offer their own corrections, however, and there have been indications of home buyers being less than satisfied with the microflat trend. According to data provided by Liber Research, prices for flats under 260 square feet rose only 78% between 2010 and 2019,

less than half of the overall market increase.

“The popularity of nanoflats has dropped in the past year,” says Joseph Tsang, chairman of Jones Lang LaSalle in Hong Kong. Some new projects have had difficulty selling nanoflats while larger apartments continued to find high demand, he says. Some buyers have even sold at a loss from what they paid to buy into new construction. “People realize that, if they could afford such a high unit cost, they might as well buy a bigger one, or buy in a more remote location with more space,” he says.

Nonetheless, the average cost of a nanoflat with less than 200 square feet rose to $3,276 per square foot in the first nine months of 2021, according to Midland Realty; that makes the smallest homes more expensive than a typical-sized flat — almost $500 more expensive per square foot.

Some civic groups have petitioned to prohibit developers from building tinier and tinier homes: The same square footage divided into two apartments reaps higher profits for the developers, while taking a toll on society as a whole. “It’s not that people really want to live in small apartments, it’s just very unfortunate that we don’t have a strong enough societal consensus that decent housing is a right,” says Ng, the Chinese University professor. “People have, year after year, really switched into a mindset that only relates to property for its exchange value, rather than what we call use value. Housing is for people to use, to raise a family, to develop social network, to build communities and to flourish as a result of that.”

Most microflat dwellers hope their situation is temporary, that by the time they are ready to couple up or have a family, they will be able to upgrade. Dr. Lee, who is currently renting his place in Kowloon, is saving for a down payment on a two-bedroom unit someday. “I live in such a small unit to save money,” he says. “I want to move out as soon as possible.”

source: bloomberg