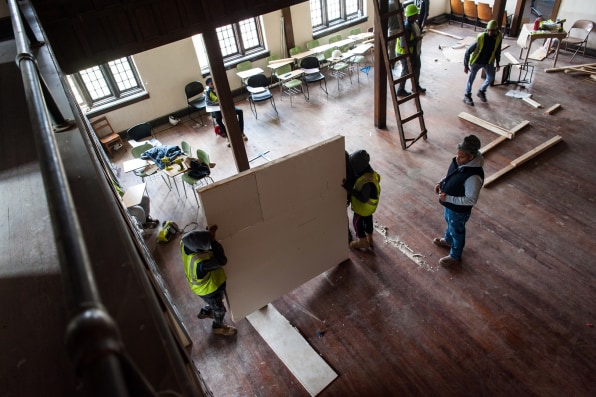

Students at Build UP remodel houses in Birmingham, Alabama, that they can then own, building generational wealth and combating blight.

When students graduate from a new kind of school in Birmingham, Alabama, at the age of 20 or 21, they could end up owning a house.

The program, called Build UP (Urban Prosperity) Birmingham, is unlike any other school in the country. Low-income ninth-graders enter to earn a high school diploma, and then an associate’s degree, while also training as construction workers through paid apprenticeships. They learn in part by remodeling houses in Ensley, the blighted neighborhood where they live. Later, they can move into the newly remodeled homes, and eventually they get the chance to buy them.

Educator Mark Martin founded the program in 2018 after seeing how ill-equipped typical schools are to tackle larger societal challenges. “The kids that I’ve worked with my entire career have all been from pretty tough backgrounds in really low-income areas with very limited options and all the challenges that come in the door with the poverty,” he says. He saw teachers struggle to help students with problems—from hunger when their parents couldn’t afford food to mental illness—and also saw the teachers feel that their efforts were futile.

The school focuses on housing, one of the basic challenges facing students and their families. Ensley was built as a neighborhood for workers at a steel mill, but when the steel mill closed, and after white families fled to the suburbs as schools desegregated, the population shrank. Some vacant houses became so dilapidated they were later torn down; others have sat empty for decades. The rental houses that are available in the area are in poor condition. “In Birmingham, all of our kids are African American, all are coming from low-income backgrounds,” Martin says. “Most are actually below the poverty line. But all of them are renting somewhere, and many are renting from slumlords—mold and mildew and just a really rotten situation.”

The program targets students who are at risk of dropping out of school and pays them a stipend as they learn how to remodel homes; novice builders get $125 every two weeks, and as students move up to different levels, that amount increases up to a max of $200. Many of the school’s regular classes are also tied to construction—a 10th-grade geometry class, for example, happens alongside shop class as students learn the math behind why roofs have certain angles or why triangles have structural integrity.

When a student is two years into the program, they and their families become eligible to move into one of the remodeled homes, where they’ll pay the same amount they were previously paying in rent. By the end of the program, after students finish their academic work and take one additional step—either getting a well-paid job in construction, transferring to get a bachelor’s degree, or starting their own business—they can get a no-interest loan to buy the house themselves. Some of the homes are duplexes, so the graduates can become instant landlords for extra income.

Martin says it’s critical to create a path to homeownership, not just an affordable place to rent. “A lot of the government’s intervention in housing is about rental assistance, or publicly owned housing that can give some money to subsidize or a free place to live, but it never changes the asset building and the equity aspect of it,” he says. “For us, it was if we’re going to change the racial wealth gaps in this country, we have to think of equity differently: not just in terms of fairness, but in terms of ownership.”

The program also gives teenagers the skills they need to be homeowners. They learn how to make repairs themselves, and how to budget. “It’s really tough to teach high schoolers about budgeting and about financial literacy if they’re flat-out broke,” Martin says. “So by giving our students biweekly stipend checks, and kind of treating them like paychecks, it gives us ground to really talk to them about budgeting and being thoughtful and planning ahead and making investments and all these things that we know, ultimately, our students need to be successful in this world.” The program also works with multiple partners in the community, including mental-health professionals for when students need extra help and a bank that helps finance the unusual home-flipping model.

The economics of remodeling houses in the area are challenging. A three-bedroom house might sell for $30,000 but require another $60,000 or more in repairs. The school began working with homeowners in a wealthy suburb nearby who frequently tear down old homes to rebuild larger mansions. Over the last year and a half, 25 owners have donated these old houses, which would otherwise have been demolished; they’re trucked to empty lots in Birmingham, where students begin to work on them. “We’re basically recycling homes that otherwise were bound for a landfill,” Martin says.

Since the school launched, students’ families have moved into seven renovated homes. Another four will soon be completed. It’s slowly beginning to change Ensley, Martin says, and that’s changing how students see themselves. “There’s nothing that builds hopefulness and agency like being a change agent in your own community,” he says. “You’re walking past blight, day in day out, on your way home from school, and driving past it, and then all of a sudden, one day, you take that blighted yard that nobody’s touched in years, and you clear all that blight, and you make it a catalyst for more change in that community.”

A contract from mortgage loan company Fannie Mae’s Sustainable Communities Initiative is helping the program spread. The team plans to soon open a second school in another neighborhood in Birmingham, and then one in Cleveland. It also plans to offer training for those who want to start similar schools. As it expands to new communities, Martin looks for areas where a network of new partners are ready to work together, including funders and construction companies that can hire students, and where the community buys into the school’s basic philosophy. “It’s this model of taking young people, who are our community’s most valuable assets, and empowering them to really take the lead on whatever direction their community needs to go in,” he says. “Our vision is that we just empower and equip youth and communities to determine their own future.”