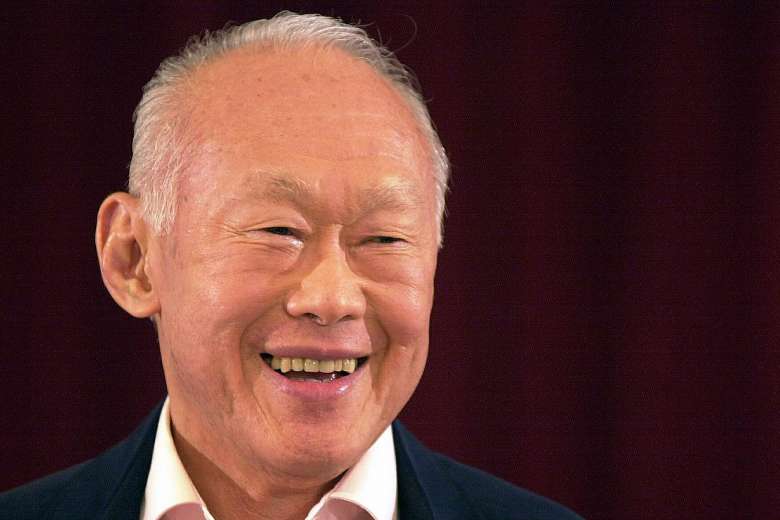

On page 393 of his book “From Third World to First: The Singapore Story,” legendary Lee Kuan Yew, Singaporean prime minister spoke about his 1966 encounter with Festus Okotie-Eboh, then Nigeria’s finance minister. describing how it went, he said:

“Raja and I were seated opposite a hefty Nigerian, Festus, their finance minister. The conversation is still fresh in my mind. He was going to retire soon, he said. He had done enough for his country and now had to looks after his business, a shoe factory. As finance minister, he had imposed a tax on imported shoes so that Nigeria could make shoes. Raja and I were incredulous. Festus had a good appetite that showed in his rotund figure, elegantly camouflaged in colourful Nigerian robes with gold ornamentation and a splendid cap. I went to bed that night convinced that they were a different people playing to a different set of rules.”

“Chief Festus” never got to see the fruit of his state-backed business strategy as he was assassinated a few days later in the military coup that effectively killed off Nigeria’s chance of achieving industrialisation in the 20th century. Five decades after his death however, the sort of half-baked, paternalistic reasoning that saw him push through a subpar policy to benefit his omimi rubber and canvas shoe factory still remains a firm fixture in Nigeria’s political arena. Ironically, it is the same people who killed him and kicked off a series of coups and counter-coups, who hold on most tenaciously, to his type of reasoning.

Nigeria’s Young Turks of 1966 are still in power 53 years later.

Recycled ideas by a recycled demographic

The most visible symbol of Nigeria’s failure to retire its class of ’66 is Muhammadu Buhari, a key figure in the events of that year who now holds the highest office in the country. Along with dozens of his contemporaries in and around Nigeria’s Defense and Security establishment, he found himself thrust into a series of offices that he was not trained, prepared or qualified for bringing to each office the same received knowledge of “Chief Festus” and his likes.

The outdated body of knowledge from 1966 has among its tenets, the idea that political problems can be solved by shooting physical bullets at them; that the economy should be subject to the whims of the state; and that state distortion of the economy to benefit private interests is a legitimate policy to benefit people in and around power. Most dangerously of all, the ideas of 1966 by virtue of their post-independence cold war era origins do not accept the possibility that they can be wrong or in need of updates.

These disastrous economic and political ideas have wreaked clear and undeniable havoc on Nigeria over the past half century, but they have never been challenged because the demographic that believes most fervently in them has retained absolute control over Nigeria’s political state in that period. President Buhari for example, who was trained to be a soldier – and nothing but a soldier – has found himself since the 70s occupying various offices including governor, petroleum minister, Head of State, PTF chairman, and now president.

In return for holding on to discredited ideas from a different time no matter how demonstrably they have failed, hundreds of individuals from Nigeria’s class of ’66 like President Buhari have gone through life being rewarded for non-achievement. This demographic of people who found themselves in political leadership circles in their 20s and 30s get to constantly fail upward from one important position to the other, seemingly destined to forever live at the public expense while expecting (and often receiving) applause for their drawn-out failure.

As we know only too well from our bitter experience, regardless of Lee Kuan Yew’s conviction, we are not actually a different people playing by a different set of rules. Nigeria has paid and is paying the huge human cost of running a huge, multi-ethnic country in the 21st using ideas that even Prime Minister Yew found preposterous in 1966.

The ideas from the class of that year turned one of the world’s biggest energy exporters into the global headquarters of extreme and multidimensional poverty. These ruinous ideas and policies turned a country that was once a global education and research hub into the place with the largest population of out-of-school children. They turned a thriving and diverse economy primed for a global breakout into a quivering mess dependent on diaspora remittances, oil prices and government borrowing, with a 70 percent debt service-to-revenue ratio. These ideas have failed woefully and they need to go.

But the Class of ’66, which has nothing to offer but these ideas is still present and does not intend to go.

It’s not a battle of the ages but…

Clearly then, we are presented with a problem. What do you do with people who know not that they know not? How do you go about changing the minds of those whose opinions are based on indoctrination in mid-20th century beliefs, and not the 50 subsequent years of evidence? How do you fix a mindset that believes that a certain way of doing things must be adhered to, even if scientific evidence says the exact opposite? The short answer – you can’t, and you probably shouldn’t even try.

According to the CIA World Factbook, approximately 62 percent of Nigerians are between the ages of 0 and 24. A further 30 percent falls between 24 and 54, which means that the overwhelming majority of Nigerians were not born anywhere within the neighbourhood of 1966. Our population is heavily dominated by an extremelyyoung demographic, which poses a challenge and an opportunity.

The challenge is that based on the most basic principles of democratic representation, Nigeria’s leaders – drawn majorly from the ’66 era – simply do not represent Nigerian people. I certainly do not feel represented by President Buhari and his geriatric co-travellers – we have practically nothing in common in terms of worldview, economic ideology, intellectual capacity, technological awareness, political consciousness and even linguistic patterns, but somehow, he is my president nonetheless.

The opportunity this weird situation presents is that since the class of ’66 have not drunk from the fountain of eternal youths as far as we know, they will have to leave the scene at some point in the not-too-distant future. When they step aside voluntarily or otherwise, the huge generational disconnect between they and everyone born after 1970 gives us the chance to effect a clean and absolute break from the political and economic ideas that have plagued Nigeria’s governance for half a century.

We are the generation that sees the rest of the world as a contemporary to interact and compete with, not a mysterious “other” to hide from inside a prison of inferiority complexes, subsidies and import bans.

We are the ones who have the capacity and imagination to build multimillion-dollar businesses using knowledge and creativity, as against politically-weighted government assistance. We are the generation of genuine entrepreneurs offering local and international value and not government tenderpreneurs who survive at the mercy of who is in political office.

We are the people who had the vision and ability to create a multibillion-dollar international entertainment industry from scratch without assistance, while the Class of ’66 – limited as they are in thought and conception – can only talk about pencil manufacturing and fractional distillation of petroleum like such things are rocket science. We are the ones who understand that mixing church and state is a fool’s errand. We are the generation that contains the human capital that has any hope of driving Nigeria forward.

Once our ‘heroes past’ have finally had their day and they mercifully stop their labour, we will have the chance to take everything we have learned over the past 50 years and use it to thoroughly deconstruct the failed system they have left behind. On the one hand, that will be a lot of work and a painful, time-consuming process. On the other hand, a popular saying has it that a society becomes great when its people plant trees whose shade, they know they will not enjoy. While Lee Kuan Yew planted trees, Nigeria spent decades enacting ideas of the “Chief Festus” variety to benefit a tiny few.

It is time to move on, and move on we will. At this point, it is only a matter of time.

Source: Businessdayng