To honour Earth Day, we’ve rounded up 10 ways architects are reshaping the built environment to benefit both people and the planet.

Architecture has a large environmental impact, with the built environment accounting for 40 per cent of the UK’s carbon emissions in 2019, according to the UK Green Building Council.

With a 2018 United Nations report warning that humanity now has less than 10 years to slow down global warming, the architecture industry is one of many to have been forced to reassess the ways in which it works.

From reducing waste and maximising urban greenery to collaboration and lobbying for change, solutions to reduce pressure on the planet are now taking centre stage.

Read on for 10 ways in which architects can contribute to a healthier planet:

Building with timber

Wood has been used to build structures throughout history. However, there has been a recent resurgence in its popularity as a construction material, due to its sustainability credentials and improvements in engineered timbers such as cross-laminated timber (CLT).

One of the biggest benefits of building with timber is that it can sequester large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere and store it within a building for as long as it stands. This can help achieve carbon-negative buildings by offsetting the carbon emissions generated through construction and operation.

It is for this reason that 3XN will use wood as the primary material in its extension for Hotel GSH in Bornholm (above) while Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios will use CLT for an office in London.

Going carbon-neutral

Making buildings carbon-neutral or, better still, carbon-negative architecture is a key concern for many architects today.

The terminology around this push is confusing but, generally speaking, a net carbon-neutral building is one that does not contribute any CO2 to the atmosphere over its lifetime, taking into account its construction, the materials used to build it plus the resources required to run it and decommission it.

A carbon-negative building is one that removes more carbon from the atmosphere than it emits over its lifetime, including the operational carbon generated by the heat and power the building consumes as well as the embodied carbon released by the extraction, manufacture and transportation of construction materials.

Confusingly, the term “carbon positive” is also used to describe the same thing as “carbon negative”.

Examples of carbon-neutral architecture include Mikhail Riches’ housing project in York that will utilise air-source heat pumps and solar panels to reduce emissions when complete.

Carbon negative buildings include Snøhetta’s Powerhouse Telemark office (above), which will generate enough surplus energy during its operation to more than compensate for both the operational and embedded carbon emitted over its lifetime.

Rewilding

Rewilding has seen a surge of interest recently as people realise that natural ecosystems are disappearing, taking with them the biodiversity that supports life on earth.

Rewilding is an approach to restoring ecosystems that let nature get on with the work itself with minimum human interference.

For architects, this offers the opportunity to take biodiversity into account both when landscaping their projects and when choosing materials, to ensure their extraction and manufacture do not lead to the depletion of natural resources.

Projects that support rewilding include architect Carl Turner’s DUT18 creative retreat in the Cotswolds region of England, which will sit in a partially rewilded landscape.

Writing for Dezeen last year, architect Christina Monteiro called for a strategy to rewild cities both to increase biodiversity and to improve the health and wellbeing of citizens.

Meeting Passivhaus standards

Since its origin in the 1990s, the Passivhaus energy performance standard has become one of the best-known ways to create sustainable architecture.

Awarded by the non-profit organisation the Passivhaus Trust, the standard encourages buildings that have high levels of insulation and airtightness so that they require minimal artificial heating and cooling.

Mikhail Riches and Cathy Hawley won the RIBA Stirling Prize in 2019 with its high-density Goldsmith Street social housing scheme (above) after designing it to meet Passivhaus standards. The win was celebrated widely, with London studio Architype stating the win “puts Passivhaus in the spotlight – exactly where it needs to stay”.

Speaking to Dezeen, Sophie Cole of Mikhail Riches said that Passivhaus design can also provide “a great basis for [zero-carbon architecture] because Passivhaus already really reduces that energy requirement”.

Reversible design

Reversible architecture ensures entire buildings can be deconstructed at the end of their life and their components reused meaning no components go to waste.

Adam Strudwick of Perkins and Will described this to Dezeen as making “every building as a kind of DIY store for the next project”.

Recent examples include Triodos Bank by RAU Architects and Ex Interiors (above), a “large scale, 100 per cent wooden, remountable office building” and a pavilion built by Overtreders W and Bureau SLA made from reusable construction materials.

BakerBrown Studio recently turned heads with its proposal to build a reusable pavilion for the Glyndebourne opera house using timber, mycelium and discarded champagne corks and seafood shells, all of which are reusable, recyclable or biodegradable.

Creating reversible architecture aligns with the aims of a circular economy – a closed-loop system where all materials are reused to eliminate any waste. Creating buildings that can be dissembled means that their components can be reused on other projects.

Encore Heureux, a studio that built a pavilion from reclaimed doors, said the idea is that “one person’s waste becomes another’s resources”.

Non-extractive architecture

Non-extractive architecture is a term coined by Italian research studio Space Caviar to express the idea that buildings should not exploit the planet or people.

“Non-extractive architecture questions the assumption that building must inevitably cause some kind of irreversible damage or depletion somewhere – preferably somewhere else – and the best we can do as architects is limit the damage done,” explained Space Caviar co-founder Joseph Grima in an interview with Dezeen.

The idea is expanded upon in a manifesto written by Space Caviar that calls on architects to design buildings that do not deplete the earth’s natural resources.

An exhibition alongside the manifesto is currently being held at cultural foundation V–A–C in Venice and Grima is joining Dezeen later today to further expand on the ideals of non-extractive architecture.

Biomimicry

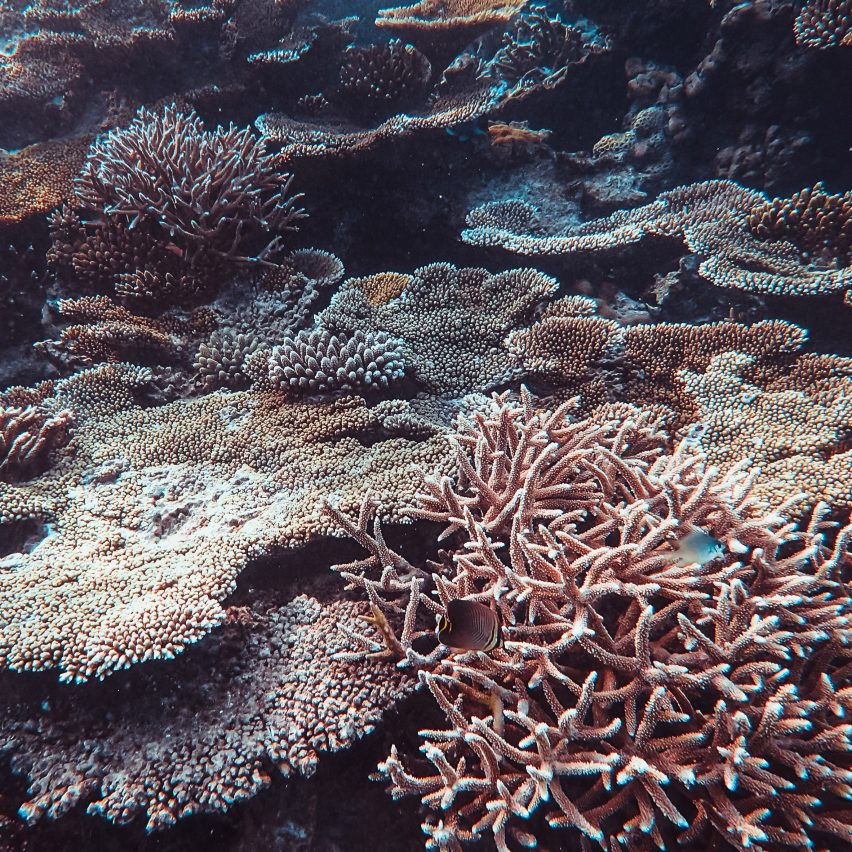

Another way in which architecture could help combat climate change is by making use of biomimicry, an approach that emulates natural systems such as coral reefs (above).

This can lead to extremely efficient structures that minimise the use of materials as well as potentially replicating beneficial processes such as the way plants use photosynthesis to turn atmospheric carbon into cellulose and other compounds.

According to architect Michael Pawlyn, entire cities could help stop climate change by removing carbon from the atmosphere by mimicking the process of bio-mineralisation, by which lifeforms such as micro-organisms in the sea turn carbon into limestone and other carbon-rich minerals.

“We need to find ways of using materials that take carbon out of the atmosphere,” he told Dezeen. “Can we learn from biology to design a built environment that has a net positive impact?”

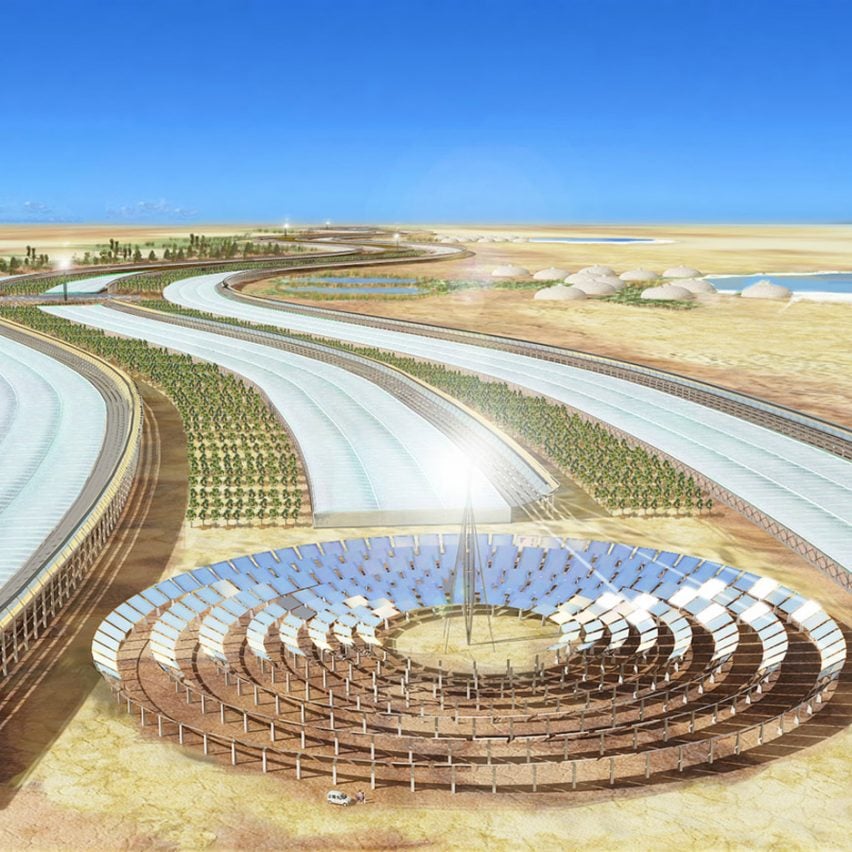

Restorative architecture

Restorative architecture, also known as regenerative architecture, refers to structures that have a positive impact on the environment.

Biomimetic architect Pawyln cites this as a key way that architects can help tackle the multiple environmental challenges of today, believing that architecture that “just mitigates negatives” is not going far enough.

His studio, Exploration Architecture, has demonstrated these ideals through The Sahara Forest Project in Qatar (above) – a seawater-cooled greenhouse that replicates a Namibian fog-basking beetle’s physiology to harvest fresh water in the desert. Any excess water it makes is used to revegetate the surrounding landscape.

Retrofitting

Retrofitting, or upgrading, is typically carried out to improve the energy efficiency and thermal performance of a building, reducing its dependence on heating and cooling, or to update a structure that may otherwise be torn down.

By prioritising the improvement of existing building stock over demolition, architects can keep materials – and the embodied carbon they contain – in use for longer, delaying the additional emissions produced by demolition.

Last month French architects Lacaton & Vassal, who are key exponents of retrofitting, won this year’s Pritzker Prize for Architecture for their “commitment to a restorative architecture”.

Other exponents include Sarah Wigglesworth, who proved the value of retrofit in the recent overhaul of her straw bale house in London (above), which has resulted in a 62 per cent reduction of its annual carbon dioxide emissions.

Elsewhere, architect Piers Taylor retrofitted his own off-grid home by upgrading all of its external fabric to meet Passivhaus standards in response to improvements in technology.

Establishing climate action groups

Architects are also addressing the impact of the built environment on the planet through grassroots initiatives such as climate action groups, in which they can raise awareness and share knowledge about climate change.

At the forefront of the industry is Architects Declare, which a group of Stirling Prize-winning architecture firms launched to call on all UK architects to adopt a “shift in behaviour”. It has a growing network of signatories across the world that collaborate through virtual events.

Another example is the UK-based group Architects Climate Action Network (ACAN), which is lobbying for more demanding legislation in the UK.

It recently launched a campaign demanding embodied carbon regulation and founded a student-focused arm that is helping combat climate negligent teaching in architecture schools.

source: dezeen