Explore what’s moving the global economy in the new season of the Stephanomics podcast. Subscribe via Apple Podcast, Spotify or Pocket Cast.

Sweden’s housing market is now hotter than ever before, exposing weaknesses in the extreme policy mix pieced together by the world’s oldest central bank.

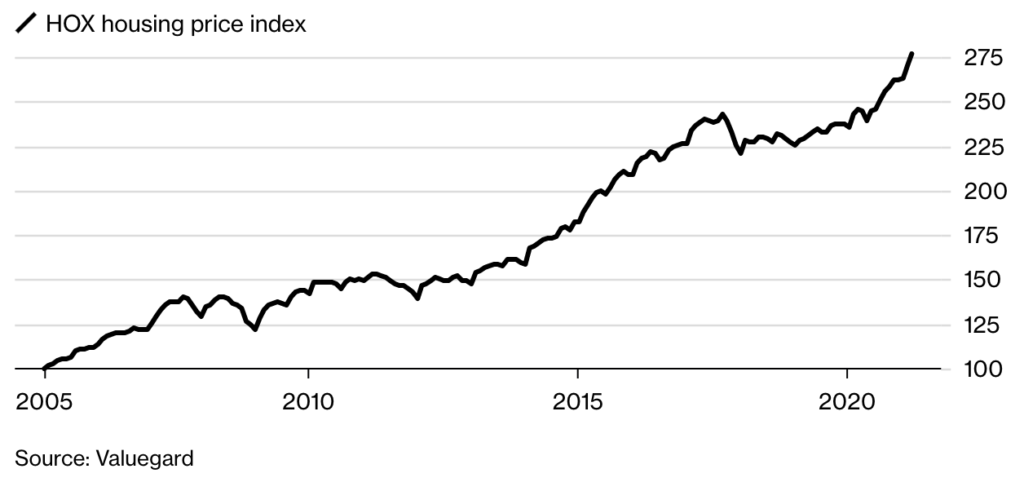

House prices in Scandinavia’s biggest economy jumped 17% in March from a year earlier to their highest ever, with a record number of homes sold in the first quarter, according to data published on Wednesday.

The price development has fed discomfort at the Riksbank which, like its peers, has had to commit to ultra-low interest rates to steer the economy through the pandemic. But the financial imbalances festering beneath the surface have prompted Sweden’s top central banker to paint a somewhat unnerving picture of what’s really going on.

“It’s like sitting on top of a volcano,” Governor Stefan Ingves said recently, referring to all the debt households have built up to pay for their homes. “I’ve been sitting on that volcano for many, many years. It hasn’t blown up, but it’s not heading in the right direction.”

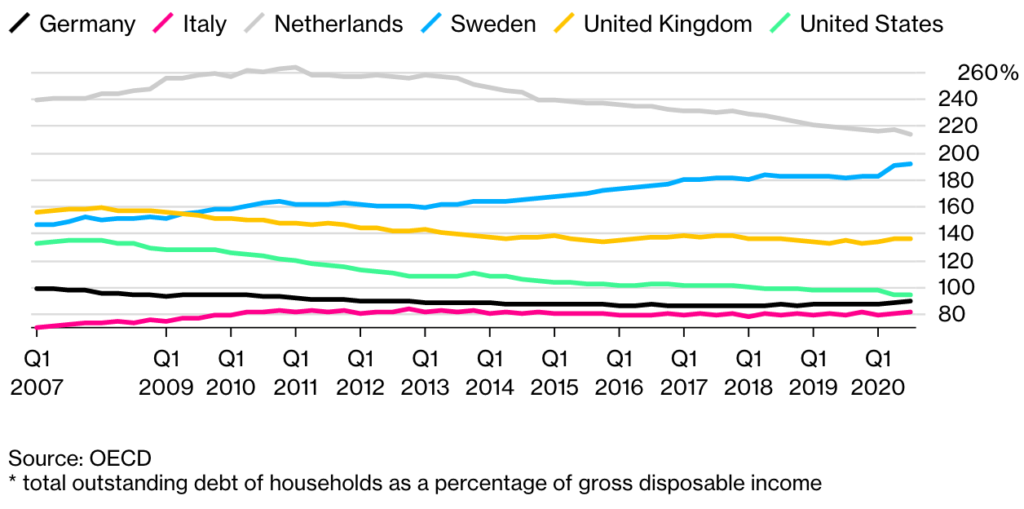

Debt Deluge

Sweden has eclipsed most peers in household indebtedness growth

Consumer borrowing in Sweden reached 190% of gross disposable incomes at the end of last year. Ingves has monitored that growing pile of debt for years, watching for tremors that could signal danger ahead.

There’s plenty of evidence Sweden’s housing market is in the middle of a boom. On Thursday, real estate classifieds portal Hemnet said it was planning an initial public offering in Stockholm this quarter. The company says it expects annual revenue growth of as much as 20%.

There’s little doubt that the Riksbank’s policies have contributed to the imbalance. The housing market development is in large part “driven by expectations of low interest rates for a long time to come,” according to Bjorn Wellhagen, the chief executive of Maklarsamfundet, a Swedish lobby group that focuses on the property market.

And it’s not just interest rates, which the Riksbank has held at zero throughout the pandemic. The bank’s purchases of the covered bonds that pay for home loans now make up the lion share of its 700 billion-krona ($81 billion) quantitative easing program.

Pressure Rising

Swedish home-price gains have accelerated during the pandemic

Policy makers at the world’s oldest central bank don’t have an easy way out, since raising rates isn’t on the cards for at least three years, according to their own forecasts. Ingves also says it wouldn’t be a big problem if inflation exceeds the Riksbank’s 2% inflation target “for a number of years.”

Source: Bloomberg