The world’s headlong dash to zero or negative interest rates just passed another milestone: Homebuyers in Denmark effectively are being paid to take out 10-year mortgages.

Jyske Bank A/S, Denmark’s third-largest lender, announced in early August a mortgage rate of -0.5%, before fees. Nordea Bank Abp, meanwhile, is offering 30-year mortgages at annual interest of 0.5%, and 20-year loans at zero.

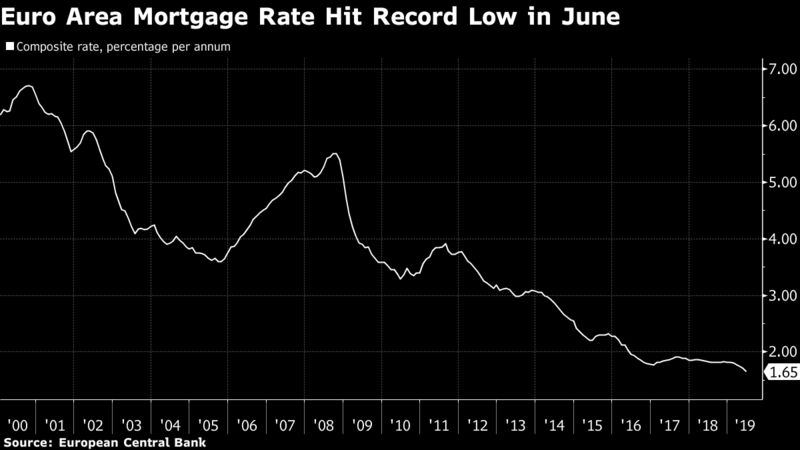

Years of easing by central banks hacked away at interest rates around the world, distorting the traditional economics of lending and borrowing. This is most pronounced in Europe, where a composite home-loan rate across the euro area fell to 1.65% in June, the lowest since records began in 2000.

While some regions have resisted the trend, borrowing costs are at or near rock-bottom in many major world markets. That’s boosted demand from homebuyers and spurred fierce competition among lenders for their business.

Here’s a snapshot of mortgage rates around the world:

U.S.

The average American 30-year mortgage rate is 3.6%, the lowest since November 2016. A resulting surge in demand for homes sent total mortgage debt to $9.41 trillion in the second quarter, surpassing the peak reached during the 2008 financial crisis. Mortgage brokers, too, are rushing to keep up with demand for refinancing: Applications are running at a three-year high.

The benefits for home buyers are muted in cities such as New York and San Francisco, however, because the boom has led to a shortage of affordable homes.

France

French mortgage rates reached a trough of 1.39% on average in June, according to Bank of France data. The country’s banking industry is extremely competitive: Many lenders have jockeyed to lure customers with cheaper offers.

Germany

German mortgage rates also reached historic lows this year, with the average 10-year loan currently under 1%. Some lenders are offering rates around 0.5%, according to Interhyp, a comparison website.

The prospect of further declines in benchmark borrowing costs could drive many mortgage rates toward zero. This may have a limited impact on the residential market, however — only 46% of Germans are homeowners, compared with an EU average of 69%.

Cheaper by the Euro

Nearly 70% of euro area countries have lower mortgage rates this year

Euro-denominated loans for house purchase, includes floating and fixed rates

U.K.

Mortgage rates in the U.K., by contrast, have been almost unchanged this year, despite a drop in overall borrowing costs amid a worsening economic outlook. The rate on a two-year fixed mortgage fell just 8 basis points from January to July, compared with a 38 basis-point drop in two-year swaps.

One reason for this, says Mark Gilbert of Bloomberg Opinion, is that the Bank of England’s regulatory arm has discouraged lenders from trying to win market share by easing standards because it’s concerned about their financial strength.

Hungary

Mortgage costs are fairly high in Hungary because regulators steered almost all borrowers away from cheaper (but less secure) floating-rate loans. A 10-year fixed-rate mortgage is currently around 5%, compared with money-market rates near zero.

The attraction of security was heightened by memories of a fashion for mortgages taken out in Swiss francs before the financial crisis. The subsequent plunge in the forint against the franc hammered as many as 1 million Hungarians.

Greece

Mortgage rates have actually risen in Greece, burdened by sovereign and corporate debts. The average floating-rate home loan was 3.08% in June, an increase of 11 basis points from a year earlier.

Greek banks’ mountain of soured loans means they have become wary of extending new credit, even when secured by a house.

Hong Kong

Mortgage rates are also climbing in Hong Kong as the political crisisweakens the appetite for loans. Both HSBC Holdings Plc and Standard Chartered Plc increased effective rates by 10 basis points to 2.48% in July, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Singapore

DBS Group Holdings Ltd., Singapore’s largest bank, is offering a three-year fixed-rate mortgage at 1.89% in the first year, rising to 2.18% in the second and third years. Floating-rate loans are set at about 1.13% above deposit rates.

Loan-to-value limits for mortgages were tightened last year to prick an incipient property bubble. Residential home prices have been recovering as foreign buyers return to the market, with private home sales jumping to the highest level in eight months in July.

Japan

The Bank of Japan’s negative-rate policy has kept home loans affordable. A 10-year fixed-rate mortgage can be had for about 0.65%, and Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank offers a rate as low as 0.53%.

This has spurred property purchases, and prices, in the larger cities, helping reverse years of decline following the bursting of the market bubble in 1991. Residential land prices in the greater Tokyo area rose 1.3% last year, while those outside major urban areas increased 0.2%, the first rebound in 27 years. Nationwide, though, prices stand at just 38% of their 1991 levels, according to the Land Ministry.

Australia

Mortgage rates have fallen about 40 basis points following the Australian central bank’s back-to-back interest rate cuts in June and July. The average standard variable rate at the nation’s big four lenders is currently 4.94%.

The decline in mortgage rates, along with an easing of lending rules and the surprise re-election of the center-right government, has fired up Australia’s housing market. Following a two-year slide, property prices in Sydney have risen over the past two months.

South Africa

The cost of a home loan remains relatively high in South Africa. Banks’ prime lending rate is about 10%, and mortgage borrowers can expect to pay anywhere from two percentage points below that rate to five points above it.

While banks are starting to extend more loans to compete for market share, mortgage rates are unlikely to drop much. Inflation is generally high, and the central bank has held its benchmark rate above 6% since 2015.

Nigeria

Nigeria has had double-digit inflation since 2016, with mortgage rates to match — as high as 30%. Those who contribute a small percentage of their income to the state-owned bank can get a much better 9% rate from the National Housing Fund.

Mortgage uptake is low because of high rates, low incomes and a long wait for government-backed loans.

Source: Bloomberg