Paying the rent for a decent home is not just a challenge for low-income families. As housing affordability increasingly creates stress on middle-income families, local governments, philanthropies, and even employers are debating new strategies to address the problem.

A Closer Look

In the past year, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and the Chan-Zuckerburg Initiative have pledged contributions ranging from $500 million to $1 billion to help build more middle-income housing in their respective backyards (literally for Google, which is proposing to convert some of its Mountain View campus to housing). The District of Columbia’s mayor, Muriel Bowser, proposed a $20 million Workforce Housing Fund to help subsidize housing for typical middle-income occupations like “teachers, police officers, janitors, [and] social workers.”

In this brief, we discuss the rationale for housing subsidies targeted to middle-income families, review past examples of policies referred to as “workforce housing,” and discuss some political and economic implications of these policies.

How are “workforce” and “middle-income” housing different from “affordable” housing?

The term “workforce housing” is most often used to indicate a program targeted at households that earn too much to qualify for traditional affordable housing subsidies. The largest rental subsidy program, housing vouchers funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), targets families making up to 50% of the median income for their metropolitan area (AMI). Households earning up to 80% of AMI are eligible to live in Low-Income Housing Tax Credit properties. Relative to these programs, workforce housing is most commonly intended for households with incomes between 80% and 120% of AMI.

The term “workforce” housing is not only imprecise, but it is also controversial: many poor households who receive federal housing subsidies are employed, so why are those subsidies not considered “workforce” housing? As we discuss below, while “middle-income housing” would be more precise language, it raises some politically awkward questions.

Some “workforce” housing programs—such as those aimed at teachers and police officers—are tied both to household income and to occupations or industries. There is a specific history of housing assistance for certain public-sector employees, stemming in part from local government requirements that those workers live within their employing political jurisdiction.

What are the pros and cons cities of attracting middle-income households?

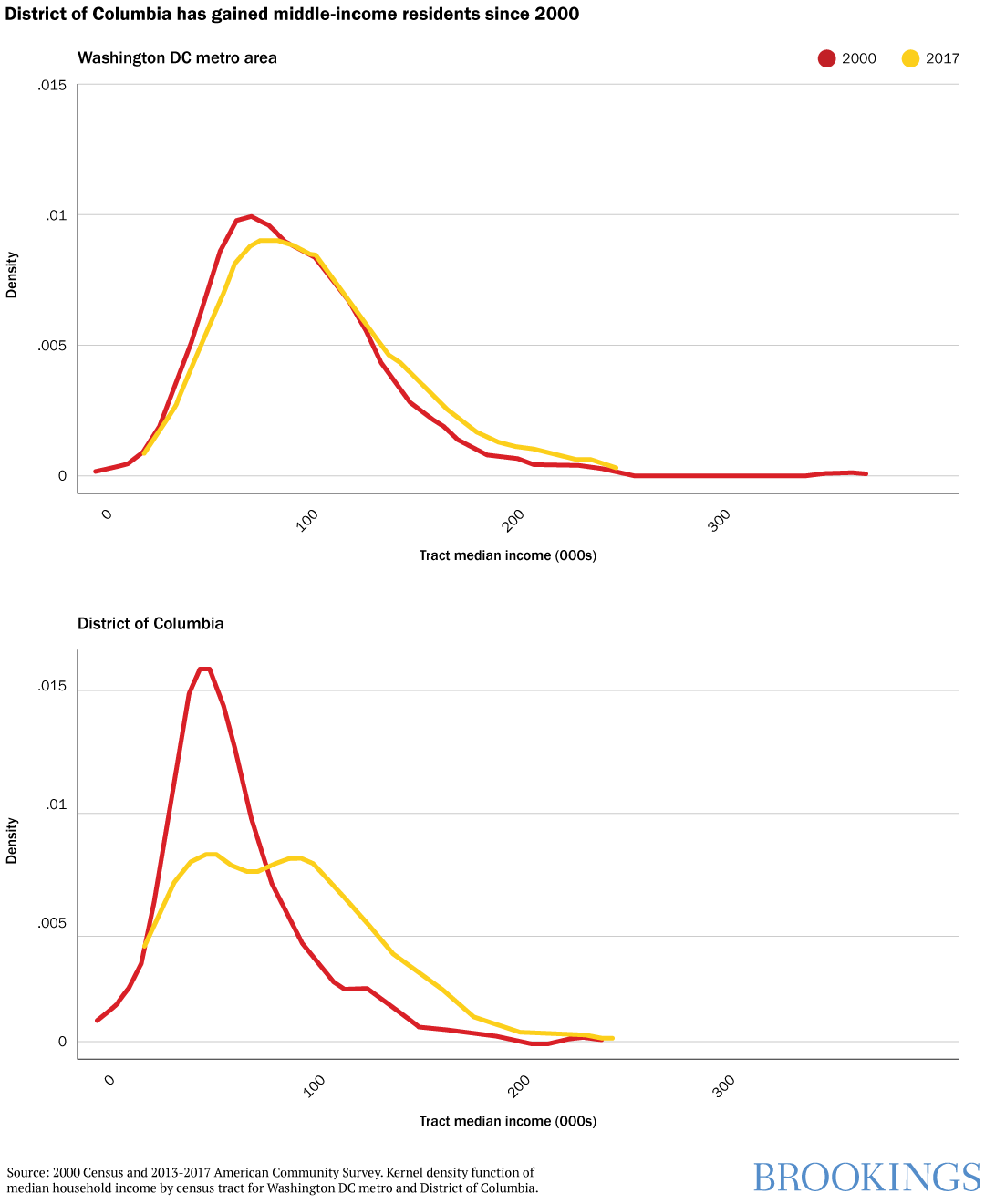

Dedicating subsidies to middle-income households may seem odd today when many cities fret over gentrification. But in the not-too-distant past, most central cities were substantially poorer than their surrounding suburban jurisdictions. Washington, D.C., offers a clear example, as we can see by comparing the income distribution of central city neighborhoods and the entire metropolitan area over time.

In 2000, about one in three neighborhoods in the Washington, D.C., metro area had median incomes between $72,000 and $108,000 (80% and 120% of AMI, respectively). Only 16% of neighborhoods in the District of Columbia were middle-income. By 2017, middle-income neighborhoods (between $80,000 and $120,000) constituted 35% of the metropolitan area and 31% of the District. Other major cities such as New York, Boston, San Francisco, and Seattle experienced similar growth in middle-income households during this period. But many mayors and city councilors have personal and professional experiences dating back to times when cities cast about for strategies to attract affluent residents from the suburbs (or keep from losing the ones already there).

Cities clearly benefit financially from having more middle-class residents. Property taxes make up the largest source of local government revenue for most cities. Cities made up of a few very wealthy residents and many poor residents face difficult choices: imposing high property tax rates may push their most affluent constituents into lower-tax suburbs, but allowing the quality of public services to deteriorate also threatens stability. When more middle-income residents move into a jurisdiction, renting or purchasing homes, cities can collect more property tax revenues from a broader cross-section of households. Middle-class residents also hit the sweet spot for consumer spending: they have more disposable income than poor households to spend on groceries, restaurants, movies, and dry cleaners—all items that are consumed locally. (Wealthy households tend to spend a smaller share of their income, so generate a smaller economic multiplier in their local area.)

It is more ambiguous whether the growth in middle-income residents creates broader social benefits for cities. On the plus side, middle-class residents can generate more pressure on local officials to invest in transportation, parks, libraries, and shared community assets. If middle-income families send their children to public schools, they bring to those schools greater financial resources, as well as social and human capital. But research shows mixed results on whether and how higher-income families interact in schools and social settings with lower-income neighbors. Moreover, an influx of more affluent households can drive up housing costs, leading to the displacement of existing lower-income residents, especially if local governments impose regulations that limit new housing development.

How have past workforce/middle-income housing programs been designed?

Middle-income and workforce housing programs have taken a variety of forms across different time periods and geographies. While not a comprehensive inventory, below we describe a few of the more notable programs.

New York City

As one of the nation’s most expensive housing markets, New York City was an early entrant into workforce housing. Two of its first examples, the Mitchell-Lama program, and Stuyvesant Town, still exist today, although both have undergone changes since their initial design.

In the 1940s, the New York and the Metropolitan Life Insurance company created an early public-private partnership to create Stuyvesant Town, a massive residential development, containing more than 11,000 apartments on 80 acres of land. The city used eminent domain to assemble land for the project and grant MetLife over $1 million in property tax exemptions annually for 25 years. MetLife built the complex to house moderate-income families, including veterans returning from World War II. From its inception, the project drew criticism for excluding Black residents and for the top-down, undemocratic process of the development.

New York State established the Mitchell-Lama program in 1955 with the Limited Profit Housing Companies Law. The program offers a combination of low-interest mortgage loans, property tax abatements, and land to encourage developers to build housing with rents that are affordable to moderate- and middle-income households (roughly the middle third of the city’s income distribution). More than 100,000 Mitchell-Lama apartments exist across New York City.

Housing for teachers, employer-provided housing

Although not widespread, some school districts and affiliated non-profits have developed workforce housing specifically reserved for teachers. This partly reflects legacies from the 1970s and 1980s, when local governments often required public employees, including teachers and emergency responders, to live in the jurisdiction where they worked. Some cities, including Chicago, still have residency requirements. Cities and towns with expensive housing often have difficulty attracting and retaining high-quality teachers, and may have less flexibility in increasing salaries. Because school quality is capitalized into local housing prices, there is a certain financial logic to local governments using public resources to subsidize teachers’ housing, especially in mostly residential suburbs. But arguments can be made that other, similarly paid occupations also provide social value to their communities. And some expensive communities (including San Francisco Bay Area suburbs) are actively hostile to building rental housing even if it would be reserved for teachers or other public servants.

Historically, many employers have provided housing to their workers: examples include the “model town” of Pullman, Illinois, dormitories for textile workers in New England factory towns, and farmers who hire seasonal agricultural workers. Often these instances have given employers undue power over their workers, with the potential for exploitation or abuse. Oddly, one remaining example of employer-provided housing can be found among elite universities in expensive housing markets: Columbia, New York University, and Stanford provide below-market apartments for selected faculty and staff.

While most of HUD’s subsidies target low- to moderate-income families, regardless of occupation, the agency’s “Good Neighbor Next Door” offers discounted home prices to teachers, police, firefighters, and emergency medical technicians in designated “revitalization areas.” The goal is to encourage households with stable employment to become homeowners in lower-income neighborhoods. And some local governments, including the District of Columbia, offer first-time homebuyer assistance to households with incomes that roughly correspond to local government salaries.

In well-functioning housing markets, middle-income families shouldn’t need subsidies

Local governments considering creating a housing subsidy targeted at middle-income families should consider the potential costs—both political and financial. Proposals to set aside scarce public resources for middle-income households are likely to face considerable opposition from traditional affordable housing advocates (and some voters), given that only one in five low-income households receives federal housing assistance. Besides the direct subsidy cost, any program imposes some administrative costs on the government agency in charge of implementation. Staff time must be allotted to process applications, and review eligibility by income and employment, similar to administering housing vouchers. There could be labor market implications of tying housing benefits to specific employers or occupations. To the extent that changing jobs might mean losing one’s housing, such programs could create disincentives for labor market mobility. Subsidies that are targeted at public-sector employees may also raise concerns: why should public employees receive subsidies that are not available to private or nonprofit employees earning the same income, and facing the same housing affordability challenges?

Housing stress on middle-income families is most acute in expensive metropolitan areas where regulatory barriers have driven up costs and restricted new development. These regulatory barriers reflect the policy choices that local governments have made; by changing the rules for housing development, local governments can bring down housing prices overall, benefitting all households. Two changes, in particular, would ease the burden on middle-income households. First, localities can reduce barriers to building a diverse housing stock in every neighborhood. Minneapolis and Oregon have recently taken steps to allow small apartment buildings by right in all neighborhoods; other states and cities are considering following suit. Second, local governments can simplify and streamline the housing development process, especially for multifamily buildings. Making the process shorter, simpler, more transparent, and less uncertain would allow more households to afford their rent without creating new subsidy programs.