Rising from the ashes of COVID-19 last year, the economy started on a bumpy ride. There was so much uncertainty about the unending pandemic and whether the fragile global recovery would be sustained.

On the domestic scene, Nigeria was neck-deep in one of its worst recessions in decades. The economy in 2020 had contracted by -6.1 per cent in the second quarter (Q2) and -3.62 the following third (Q3). With dipping revenues, the government could not do much to inspire confidence in an economy that was losing more jobs than it was creating.

Indeed, there was a consensus that the recession would be short-lived but sharp disagreement on the speed of recovery – a convoluted U- or V-shape recovery? There was fear that a prolonged shock could trigger a deeper slump or depression. But fortunately as predicted by some experts, the economy had exited recession earlier than expected. This was confirmed by quarter four (Q4) 2020 gross domestic product (GDP) data.

A fragile growth

Amid concern about rising fiscal risks, the country’s output, in Q2, broke a six-year record, jumping by 5.01 per cent year-on-year (YoY) to consolidate the fragile growth that started in Q4 2020. The growth was roughly twice as high as any other previous quarterly performance in the life of the current administration.

The leg-up performance came two quarters after the country exited one of the deepest recessions in its history. The economy had caved in by -6.1 per cent and -3.62 per cent in Q2 and Q3 2020 respectively to confirm the second recession since President Muhammadu Buhari took over the country’s political leadership.

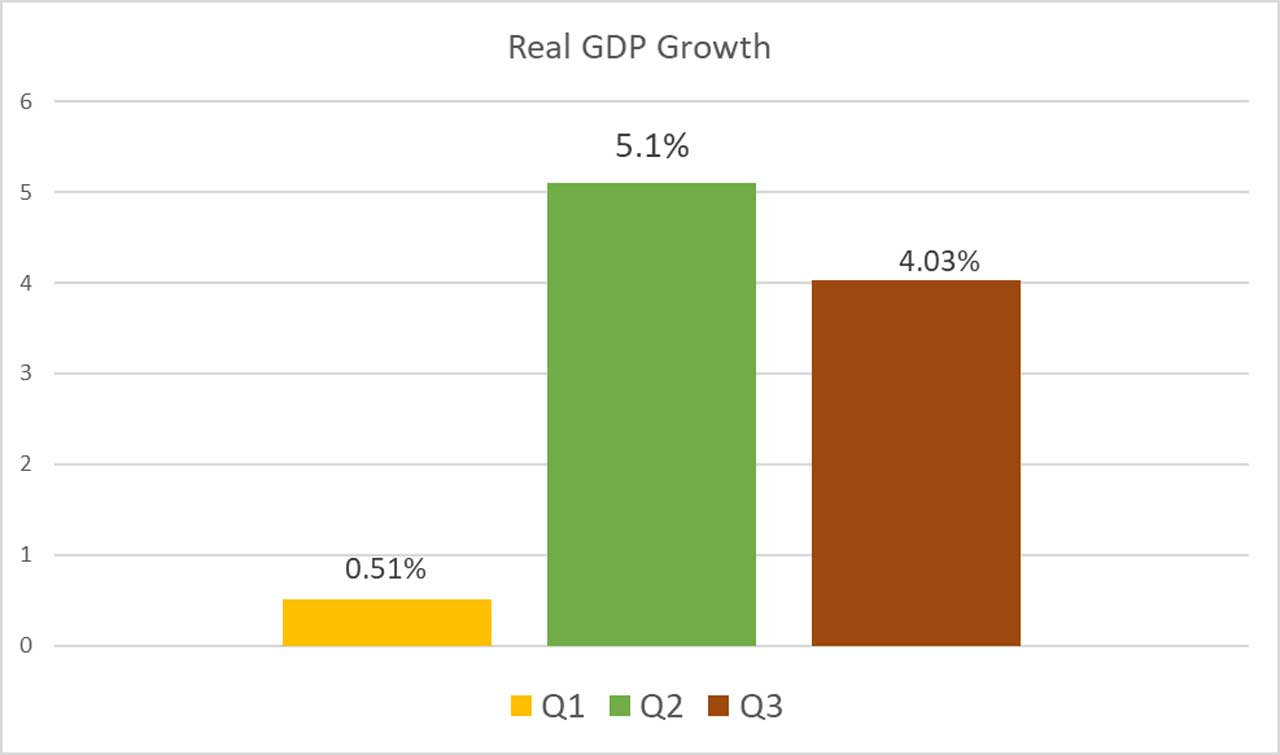

The recession ended with a near-zero positive growth – 0.11 per cent year-on-year (YoY). First quarter 2021 growth figure was also positive, though only enough to take it out of stagnation. The value of production added 0.51 per cent in real terms YoY. But there was a significant leap in the Q2 2020 data even though some economists dismissed the expansion as a fallacy of broken windows.

The growth was mainly influenced by the base effect of the deep hole of Q2 2020 when the economy was completely redundant following restriction in movement. The transport sector underscored the fallacy of the growth. Coming from a complete shutdown in the comparative quarter of 2020 during which it posted -49 per cent growth, it jumped by over almost 77 per cent in Q2 2021.

In absolute figures, the composite growth fell short of taking the critical sectors of the economy to the pre-COVID era. Manufacturing, for instance, was still tottering on the brink of total collapse despite the reported growth. For instance, the output value of the sector only increased from N1.4 trillion in Q2 2020 to N1.45 trillion in Q2 2021 and played a disappointing role in reducing the fast-growing unemployment rate.

In quarter three (Q3), the growth moderated to 4.03 per cent. While Q4 data are yet to be released, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated the annual growth at 2.6 per cent, which is about the same as the average population growth rate in the past decade. A professor of economics at the University of Ibadan, Adeola Adenikinju, said the country must aspire to grow its economy at a much faster speed to experience real economic development.

Unemployment, a time bomb

Rising unemployment is one of the social consequences of stagnant or negative gowth. There is no up-to-date data on the state of human capital utilisation but the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Q4 2020 survey released towards the end of Q1 2021 showed the unemployment rate has reached its highest level in over a decade. According to the data, the unemployment rate rose from 27.1 per cent in Q2 2020 to 33.3 per cent in six months, earning the country a spot on the list of countries with the scariest job data.

The report said 23.2 million out of 69.7 million Nigerians in the labour market were jobless. Perhaps, the worst aspect of the data was the rate of employment among the youth population. According to the data, unemployment in Nigeria was worst among youths between 24 and 35 years where 7.5 million or 37 per cent of the number of members of the group were jobless.

Female unemployment was higher with 35.2 per cent while that of the male was 31.8 per cent. The trend was different in the case of underemployment with 24.2 per cent reported as against 21.8 per cent for the male counterparts.

Also, the unemployment rate among rural dwellers is 34.5 per cent while that of urban dwellers was 31.3 per cent. In the case of underemployment, rural dwellers reported 26.9 per cent while the rate among urban dwellers was 16.2 per cent. Whereas a large number of Nigerians were without jobs, the cost of living triggered by fast inflation also sent shockwaves, thus worsening the misery index of the country.

Nigeria’s ‘decelerating’ inflation figure

In March, headline inflation hit a five year high of 18.17 per cent, over 100 per cent higher than the Central bank of Nigeria (CBN)’s target. It had never been that bad since January 2017. The inflation crisis started over two years ago following the land border closure but worsened last year with the food inflation almost touching 23 per cent in March before a gradual retreat.

The year opened at 16.47 per cent inflation, which seemed to accelerate monthly through the year. But NBS data said moderation started after March, setting the stage for a seven-month consistent deceleration up till November. The figure closed at 15.4 per cent but many experts bucked at the official declaration.

While NBS monthly figures pointed to easing of the inflation, Nigerians groaned under astronomical rise in prices of essential commodities. An independent survey by The Guardian suggested that prices of essential items increased by between 50 and 150 per cent in the year. Also, a report by the Lagos Business School also put the YoY average change in prices of consumer goods at 94.7 per cent – from December 2020 and December 2021.

The controversy ignored, the official figures released by NBS last year were the worst inflation figures in over a decade. The last time the country’s food inflation rose to 20 per cent was February 2009. But last year, it exceeded that mark by almost three percentage points. It was also worrisome that states considered as food baskets of the country were consistently atop the food inflation figures.

The wide differential between core and food inflation also raised concerns about the widening income inequality as well as the deterioration in the efficiency of the transportation system. In November, for instance, the gap was above seven percentage points. Some economists have suggested that the widening gap between core inflation and food inflation underscored the severity of the pressure faced by poor households last year.

Unending currency crisis

Historically, Nigeria’s inflation is an increasing function of the naira exchange rate. The important dependent nature of the economy is a possible explanation. Last year, Nigerians had a full ‘dose’ of the twin-challenge of foreign exchange and essential commodity price crises.

The year opened at N475/$ at the parallel market but closed at N565/$, implying that naira traded against dollar at a discount of 19 per cent at the black market. At the official investors’ and exporters’ (I&E) window, the local currency took a haircut of over six per cent. It started the year at N410/$ and closed trading last week at N435/$.

It was an eventful year on the policy side as well. First, the apex bank replaced what used to be known as the CBN official rate, which was used for government transactions, with an I & E window otherwise called the Nigerian Autonomous Foreign Exchange (NAFEX) window. This followed an extended reform of the remittance administration and payment process, which started in 2020.

Also, the weekly funding of bureau de change (BDC) operations and the handing over of business/personal travel allowance (B/PTA) dollar sales to commercial banks. The rejigging, notwithstanding, the crisis in the FX market has continued into the New Year.

Rising debt burden

Nigeria sank deeper into the morass of debt overhang, raising questions about sustainability, appropriateness and utilisation of the borrowed money. Despite the huge outstanding debt, the government said the country had no alternative to continuous borrowing. Nigeria’s public debt stock stood at N32.9 trillion as of the end of 2020 but increased by N5.1 trillion in nine months to reach its current N38 trillion. The profile increased by 15.5 per cent in three quarters.

But the debate last year was more about sustainability rather than the size of the national debt. In the first quarter of last year, the country’s debt-to-revenue ratio was about 73 per cent, which the President of the African Development Bank (AfDB), Dr. Akinwumi Adesina, said must be tackled to grow the economy.

Of course, there is no break from the challenges as the country begins another year. But some experts said a rare fiscal discipline unseen among the national economic team in recent years could steer the ship to a comfortable voyage.