The Singapore Institute of Landscape Architectsorganized nine technical tours as part of the very well-run 2018 World Congress of the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA). Tour 1, “Remaking Heartlands in Singapore,” was prepared with the assistance of the Housing and Development Board and featured sky gardens, green roofs/walls, and sustainable stormwater management for high-rise public housing in Singapore.

Historical Background

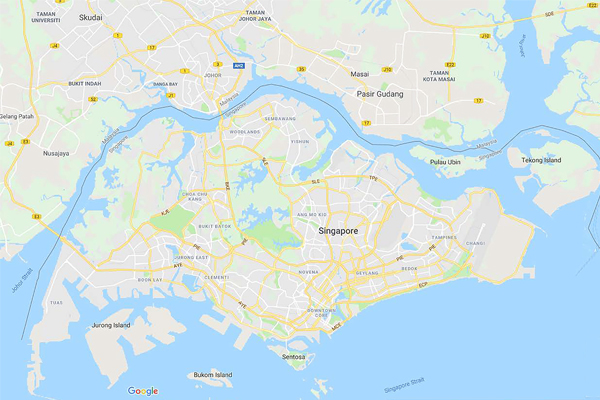

The Republic of Singapore is a multi-ethnic Chinese, Malay, and Indian (mainly Tamil) island city-state connected by two causeways to the southern end of the Malay Peninsula, a 5-hour drive from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. In 2017 it had a population of 5.61 million (and rising) on 709 square kilometers (274 square miles) for a density of 7,796 per km². By way of comparison, Chicago has a population of 2.7 million (and falling) on 589 square kilometers (227 square miles) for a density of 4,613 per km². (Population density figures may vary depending on whether the water area is included.)

How a city-state that once had, according to the British colonial government’s Housing Committee Report of 1947, “one of the world’s worst slums” became the land of Crazy Rich Asians is a fascinating success story.

In 1819, Sir Stamford Raffles of the British East India Company founded a trading post that became the modern city. It was part of the British Empire except for Japanese occupation during World War II. After the war, British control weakened, and Singapore, Malaya, and the British territories in northern Borneo gained increasing autonomy that culminated in independence in 1963. Singapore was briefly part of the newly formed Federation of Malaysia, but for political, economic, and cultural reasons, it became a separate city-state in 1965. Although Singapore lacked natural resources, it evolved from a developing nation in the 1960s, to a newly industrialized country in the 1980s, to what is now one of the world’s most successful countries. One in six contemporary Singaporeans is a millionaire—not counting possessions and real estate (which is among the most expensive in the world).

The development process was, however, difficult, and housing was one of the greatest challenges. Urban dwellings were mainly in the form of shophouses, which were crowded, two- or three-story apartments over ground floor shops. Outside the urban area, there were traditional Malay or Chinese villages along with a few large estates for the wealthy.

Beginning in the 1920s, the British colonial government attempted to address the serious housing shortage with affordable public housing developed by the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT), but it was ineffective—constructing only 23,000 units in 32 years. By the end of World War II, the housing shortage, aggravated by wartime damage, was at a crisis level. The situation was worsened by an influx of people fleeing to Singapore both because of attacks by communist guerrillas during the Malayan Emergency of 1948 – 1960 and the British response, which included the forced relocation of half a million people, mainly ethnic Chinese, from rural areas of the Malay Peninsula.

During the period of increasing self-government preceding independence, the SIT was replaced by the Housing and Development Board (HDB). A 1966 HDB report estimated that “300,000 people lived in squatter settlements and 250,000 lived in squalid shophouses in the Central Area.” The HDB faced monumental challenges. Its first priority was to build as much housing as possible since it estimated that an average of 14,000 units per year were needed. The focus in the beginning was mainly on low income rentals. However, the government introduced the Home Ownership Scheme in 1966 to assist people in buying their flats (apartments) on 99-year leases. In 1968 a further incentive was added by allowing people to use their savings from the Central Provident Fund(national pension plan) for their down payment. Initially this effort was not successful in enticing squatters out of their informal settlements until there was a major fire in one that left 16,000 people homeless.

Prior to the creation of the HDB, Singapore’s housing had been mainly in the dense but low-rise urban center on the southern end of the island and squatter settlements nearby. The remainder of the land was largely rural with Malay and Chinese villages. Because land was limited and the city center was too congested, the HDB shifted to high-rise, high-density developments, and these were gradually distributed around the island with the creation of a series (now 25) of satellite new towns (or “estates”) linked by a growing rapid transit system.

The prototype housing estate has 60,000 dwelling units with an average of 92 per hectare (37 per acre). It is largely self-contained with commercial uses, schools, institutions, parks, sports facilities, and in some cases (non-polluting) industries.

The transition from villages to high-rise living was, in the early days, traumatic for some. A few farmers tried to bring their chickens and pigs with them. Even urban Singaporeans were uncomfortable living above the 4th floor at first. The older public housing designs had been very basic 12-story apartment blocks. More recent buildings are 30 to 40 stories. People have now grown accustomed to these and actually prefer the 16th to 30th floors [Yuen, Belinda. Squatters no more: Singapore social housing, Global Urban Development Vol. 3, Issue 1 November 2007].

The Current Situation

Rising affluence in Singapore has brought rising expectations. The HDB became concerned that people on upper floors of high-rise blocks were too isolated from nature. This evolved into the “Housing-in-a-Park” concept with public gathering areas on green roofs—some with community gardens, sky gardens at 10-story intervals up the building, and landscaped plazas over underground parking garages. Green walls are also common.

The sky gardens have landscaped areas and facilities including “3G” 3-generation playgrounds with children’s play structures, adult fitness equipment, and seating areas so the different generations (and races) can interact, and parents or grandparents can supervise the children.

Shopping, services, food courts, and public gathering areas are provided on the ground level and second floor.

Transportation Infrastructure

The satellite towns/housing estates are well connected by public transit. Singapore now has five mass rapid transit lines (plus one under construction and two more in planning) and three light rail lines. These, supplemented by bus lines, serve the whole island. Automobile owners, however, face special challenges in Singapore.

To purchase a car, Singaporeans need to submit a bid in an online public auction for a Certificate of Entitlement. The current price is about $36,500 USD, and it must be renewed at the going rate every five or ten years. Registration fees, excise duty, and taxes can add up to more than twice the base price of the car (depending on size), so even a modest sedan costs an average of over $77,000 USD, not counting the Certificate of Entitlement, insurance, gasoline ($6.50 per US gallon), parking, and congestion-based daily road tolls.

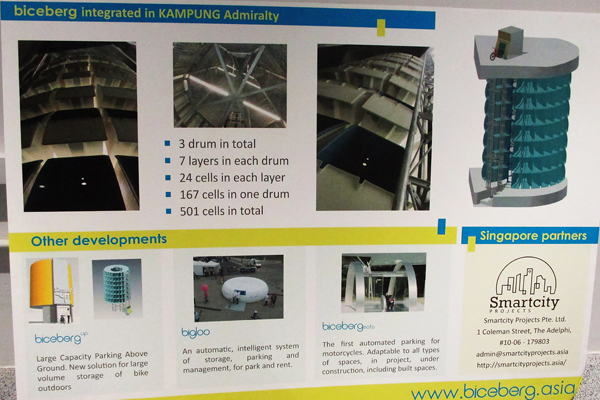

In spite of the tropical climate, active transportation with bicycles is becoming more popular. In fact, to control the clutter of bicycle parking in the housing estates, automated, multi-story bicycle parking systems are being introduced.

Stormwater Management

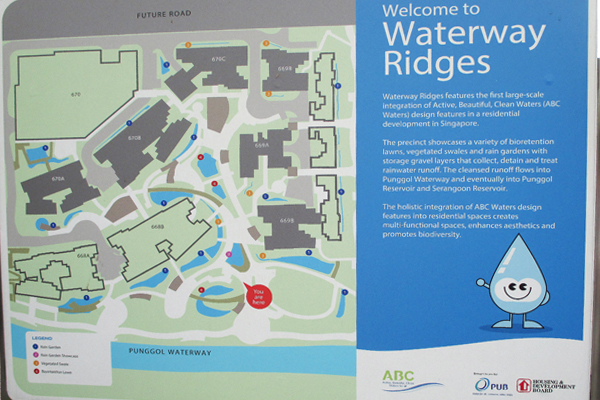

There are three seasons in Singapore: Northeast Monsoon, Southwest Monsoon, and “unstable inter-monsoonal period.” The mean annual rainfall is 2,165.9 mm. Much of the rain is in heavy downpours, so effective stormwater management is essential. This was formerly done with massive monsoon drains, but more environmentally-friendly techniques are now being used. The Waterway Ridges housing estate was developed implementing the “Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters” (ABC Waters) concept promoted by the Public Utilities Board (PUB) and HDB. Singapore needs to collect its rainfall, keep it clean, and direct it to reservoirs that provide most of the city-state’s potable water. Almost 40% is now imported from Malaysia across the causeway, but those contracts expire in 2061.

The PUB/HDB sign says, “The precinct showcases a variety of bioretention lawns, vegetated swales and rain gardens with storage gravel layers that collect, detain, and treat rainwater runoff. The cleansed runoff flows into Punggol Waterway and eventually into the Punggol Reservoir and Serangoon Reservoir. The holistic integration of ABC Waters design features into residential spaces creates multi-functional spaces, enhances aesthetics and promotes biodiversity.”

Conclusion

Under British colonial rule, “the housing problem was regarded as something of a transitory phenomenon that would disappear as the economy grew. Such an attitude was convenient as it provided the basis for taking little or no action on housing” [Yuen, Belinda. Squatters no more: Singapore social housing, Global Urban Development Vol. 3, Issue 1 November 2007]. This was based on a “trickle-down” economic philosophy. After independence, the Singapore government took the opposite approach—seeing housing as a human right and using effective, corruption-free, centralized planning to achieve it. The result was: not only did people get housing, but it stimulated the economy to the point where Singapore has become one of the most successful countries in the world. Over 1 million units have been built, housing more than 80% of the population, and about 90% of these people own their homes.

As living standards rose over the years, there was also an increasing awareness of the importance of landscape architecture to the environment and to people’s well-being. The Housing Development Board has produced a useful Landscape Guide that can be viewed and downloaded as a free e-book.

To see a hopeful vision for the future as a counterpoint to the dystopian world of Blade Runner, visit Singapore.

Source: thefield.asla.org

microsoft project 2016 lizenz kaufen