Last series, we discussed the ethnic undertones of the 1951 general election and their consequences on Igbo-Yoruba relations. Today, we’ll discuss the 1953 self-government motion which highlighted Nigeria’s north-south fault line and almost led to the break-up of the country.

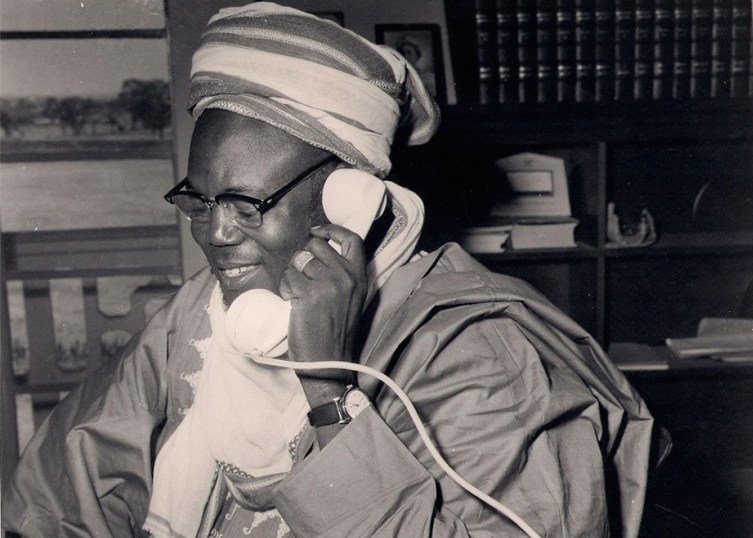

In March 1953, Anthony Enahoro of Awolowo’s Action Group party motioned for Nigeria’s federal House of Representatives to endorse the attainment of independence in 1956 as a primary objective. Azikiwe’s National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) party supported the motion, but Northern members led by Ahmadu Bello opposed it. Bello suggested replacing “1956” with “as soon as practicable.” Addressing the House, he stated:

“It is true that we politicians always delight in talking loosely about the unity of Nigeria. Sixty years ago, there was no country called Nigeria. What is now Nigeria consisted of a number of large and small communities all of which were different in their outlooks and beliefs. The advent of the British and that of Western education has not materially altered the situation and the many and varied communities have not knit themselves into a composite unit.”

Bello dismissed declarations of Nigerian unity as empty rhetoric, asserting the country’s inhabitants were no more a nation in 1953 than they had been before the British arrived. He then went further, stating that “the mistake of 1914 has come to light.” In his memoirs published a decade later, Bello described his statement characterizing the 1914 amalgamation of Nigeria as a “mistake” as the “most important” political speech he ever made.

Justifying northern opposition to early independence, Bello argued there had been too few educated northerners at the time. Northern elites feared that if independence came as early as 1956, southerners would dominate their civil service. In their view, this would be dangerous because southerners could not be trusted to do the fair thing. Instead, they would most likely exploit northerners and divert resources to the south, leaving the north ever poorer and weaker. Bello stated:

“If the British administration had failed to give us the even development that we deserved and craved so much- and they were on the whole a very fair administration- what had we to hope from an African administration? The answer to our minds was quite simply just nothing beyond a little window dressing.”

Northern elites trusted the British “to do the right thing” more than they trusted southern Nigerians. Southerners described this as the result of British brainwashing, but northerners argued their mistrust stemmed from real-life experiences with southerners.

After northern politicians blocked the 1953 self-government motion, southern leaders accused them of being colonialist lackeys. Northern politicians were booed and insulted by southern crowds on leaving the House of Representatives’ building in Lagos. The abuse continued throughout their trip back to the north, with angry southerners awaiting them at each train stop.

Following this, northern elites favoured seceding from Nigeria and were restrained solely by practical considerations. The north was landlocked and dependent on southern coastal links to transport its goods. Northern elites worried southern leaders might block transportation of goods across their lands if the north seceded. Awolowo threatened as much, saying if Britain let the north secede “we [the west] shall declare our independence immediately and we will not allow the north to transport their groundnuts through our territory.” Groundnuts were a key northern export at the time.

Nevertheless, northern leaders declared an 8-point programme entailing de-facto secession from Nigeria, only to be dissuaded by the British who feared a domino effect. At the time, Governor-General Macpherson wrote to Thomas Lloyd, Undersecretary of State for the Colonies, warning that “if Nigeria splits, it will not be into two or three parts, but into many fragments.”

In this atmosphere, AG leaders decided on an “educational tour” of the north to promote their self-government motion. Inter-ethnic violence eventually erupted in Kano, leading to 277 casualties, including 36 deaths – 15 northerners and 21 southerners. After the Kano riots, Oliver Lyttleton, Secretary of State for the Colonies, informed London it was clear the regions could not work together in a tightly-knit federation and Nigeria needed to be decentralized.

Constitutional conferences involving Nigerian leaders were held between July 1953 and February 1954. A memo written by Lyttleton to the British cabinet during heated debate over the future status of Lagos gives us interesting insight into the thinking of Britain’s highest-ranking colonial official at the time. In the memo, Lyttleton described “Hausa-Fulanis” as “Muslims and warriors, with the dignity, courtly manners, high bearing and conservative outlook which democracy has not yet debased.”

He then described Yorubas and Igbos as people “with higher education, but lower manners and inferior fighting value, somewhat intoxicated with nationalism, though loyal to the British connection at least so long as it suits them.” Advising the British cabinet on what to do regarding Lagos, Lyttleton wrote:

“The north with their deep but already somewhat shaken trust in the British and distrust of their ‘brothers’ in the West and East fear that greater autonomy now suggested for regions will lead to the West seceding when it suits them, especially as the West incorporates Lagos, at once the commercial and political capital and only effective outlet to the sea for the trade and commerce of the North… The North now insist on Lagos being a federal area under separate administration to safeguard it from becoming a Yoruba preserve and to make sure their access to the sea remains open… We cannot let the North down. They are more than half the population, more attached to the British and more trustful of the colonial service than the other two…if my colleagues agree, I shall state that we have decided to excise Lagos from the West… to act otherwise would be to alienate our [northern] friends, probably drive them into secession, to cast aside our responsibilities and to leave a dismembered Nigeria to settle its own differences perhaps with the spear.”

Lyttleton’s memo provides evidence supporting the claims of southern leaders that the north was favoured by the British during Nigeria’s constitutional negotiations, at least in this particular case.

The 1953/54 conferences produced the Lyttleton Constitution which established a firmly federalist system in Nigeria. The House of Representatives would now have jurisdiction over certain specified issues while jurisdiction over everything else devolved to regional assemblies. Each region would have its own Premier, with his own cabinet of ministers. The north retained its 50 percent quota in the federal legislature. Each region could attain full internal self-government by 1956, if it so wished.

The years 1952 to 1954 were characterized by northern fears of southern domination in a post-British Nigeria, southern frustrations at the north slowing the march to independence, further solidification of ethnic and regional identities, and realisation federalism was the only realistic system for such a diverse country. The 1954 Lyttleton Constitution reflected a tacit admission by all the relevant actors that Nigerian unity was more aspiration than reality, a situation which persists 65 years later. Perhaps we shall stop there for today. Next series, we’ll discuss the late 1950s and the final march to independence. Till then, take care folks!