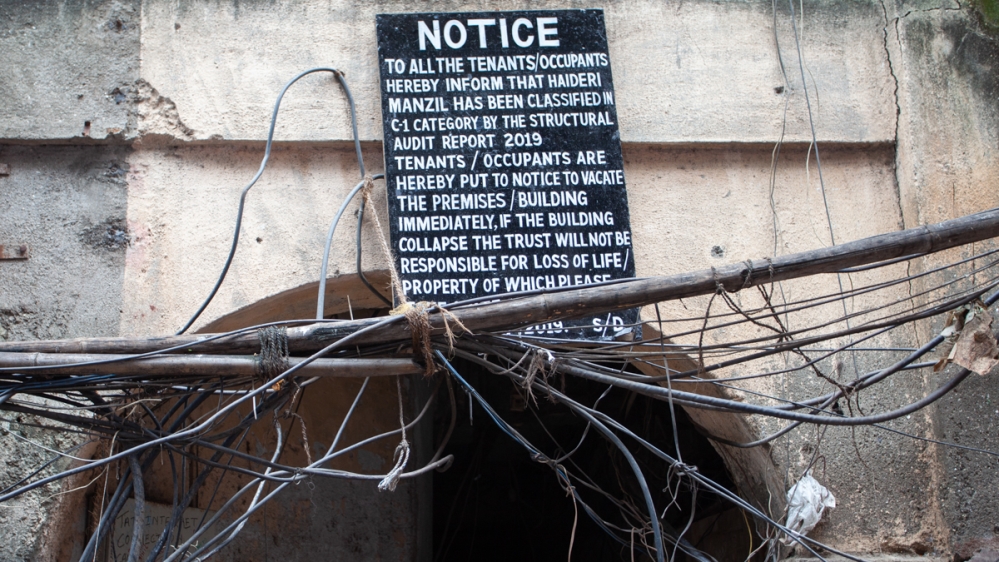

At the entrance of Hyderi Manzil, a four-storey building in a congested southern Mumbai neighbourhood, was a notice painted in white: “If the building collapse, the trust will not be responsible for loss of life.”

Arshi Syed, 34, points to one of the many holes in the walls of the corridor, outside her one-room house.

“The structure is so weak, rats have eaten into it,” she said. “My family and I stay awake at night, especially during the monsoons, in case the building is ready to fall.”

But despite the risks, along with 21 families, Syed continues to live in the building in Dongri, a predominantly Muslim locality.

Over the past five years, 234 people have lost their lives while 840 have been injured due to building collapses across Mumbai.

A recent report by IndiaSpend, a non-profit organisation tracking data across India revealed that there are 14,207 buildings that are vulnerable to collapse in the city.

Like Hyderi Manzil, they are more than 50 years old and could fall due to age-related instability and a lack of maintenance.

“Residents don’t want to leave,” said Vaishali Gadpale, spokesperson or the Maharashtra Housing And Area Development Authority (MHADA), the civic body that manages the maintenance and redevelopment of vulnerable buildings. “They fear that it will take a long time before they can return to their homes if they are evicted, or they will never return at all.”

MHADA provides “transit camps” or alternative accommodation to residents of dilapidated buildings, which are known as “cess properties”.

While the organisation collects a tax from the landlord to upkeep the building, several people Al Jazeera interviewed said they had not benefitted.

![The notice outside Hyderi Manzil declared unsafe to live in and has asked it's tenants to evacuate immediately. [Rashi Arora/Al Jazeera] India's Financial Capital Is Crumbling](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2019/9/8/6b1fdb0859504e13baf7640fde29ca39_18.jpg)

M V Damani, a 70-year-old resident of Kesarbai 25C, whose building in Dongri was declared dangerous in 2017, is still waiting to be assigned to a camp.

“I have sent my application to 14 different branches of MHADA so they can provide me with all the options of accommodation they have for me. I have followed up with several officials over several months,” says Damani a retired chemical engineer and now a right-to-information (RTI) activist. “Still I have received no response.”

He described a similar sense apathy among public bodies when most of the tenants in his building found unauthorised people occupying their transit camp – a common practice according to residents of vulnerable properties.

“MHADA had no procedure on how to solve this problem,” said Damani, who helped his neighbours file complaints. “After several attempts, when there was no action by civic authorities, people were tired. Those who could afford it rented houses elsewhere and others went to live with relatives. Many even chose not to apply for transit camps because they had seen how others had suffered.”

Meanwhile, there are no signs of redevelopment on Damani’s building. It is decaying with locks on all its homes, inhabited by stray dogs and cats.

Syed fears her building will end up in a similar state.

“Many residents in our building left their homes hoping that in time the building would be reconstructed,” she said. “But over 10 years have passed and nothing has changed. Those tenants have returned, having wasted rent money elsewhere, to the same broken homes. So what is the point in me leaving too?”

Lack of funds, will to redevelop

To avoid being rendered homeless in a city with soaring real-estate prices, people living in vulnerable properties, who usually come from low-income communities, procure a no-objection certificate, or NOC, from MHADA – according to which residents agree to undertake the redevelopment of the building themselves.

But a lack of funds make building a safe home challenging.

Under the city’s restrictive rent control acts, rent of all buildings constructed before 1965 has been frozen at pre-1965 rates, with some held at pre-1940 levels.

This means that monthly rents can be as low as 100-300 Indian rupees ($1.40-$4.2), say residents.

![The site of the building Kesarbai 25B in Dongri, which collapsed in June. Adjacent to it 25C where MN Damani lived. [Rashi Arora/Al Jazeera] India's Financial Capital Is Crumbling](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2019/9/8/e931da53e5244d309bd9fde90e945f2d_18.jpg)

Landlords then become reluctant to fund overhauling costs of the buildings themselves.

“We aren’t asking for free redevelopment,” said Syed, whose father is an embroiderer. “My family and others in the building are willing to bear 40 to 50 percent of the costs but the rest needs to be funded by the government or the building trustees. We cannot afford it.”

Then, there are the run-down buildings that escape civic intervention completely.

Early this year, Damani contacted the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (BMC) for the Unique Identification Number (UID) of Kesarbai 25B – a building adjacent to his house which was in a similar state of dilapidation.

When Damani noticed that both wings of Kesarbai had the same EID number, despite being two separate structures, he raised the issue with the authorities. He said he was ignored once again.

Later in June, Kesarbai 25B collapsed, killing 14 people and injuring nine others. It was later identified as an unauthorised building and the BMC responsible for tracking down illegal structures was held accountable.

“They [the BMC] had no record of Kesarbai 25B,” said Damani. “So an eviction notice never reached the building that collapsed.”

![The site of the building Kesarbai 25B in Dongri, which collapsed in June. [Rashi Arora/Al Jazeera] India's Financial Capital Is Crumbling](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2019/9/8/0e0a29af3b1b4001956cc2694970468e_18.jpg)

Shakeel Ahmed Sheikh, an activist, said there are hundreds of illegal structures at risk of collapse around Dongri, with unauthorised floors and terrace rooms built on top of several dilapidated buildings.

Sheikh believes the government should spearhead “cluster development” – a scheme which would allow MHADA to redevelop clusters or entire neighbourhoods of ramshackle buildings together.

This scale, he said, would attract reliable developers to invest, as many stay away due to the logistical complications of developing old low-rise buildings which are barely 304-365 square-metres (1,000-1,200 square-feet).

“The problem is there is no political willpower to implement such policies,” said Sheikh.

Back in her crumbling building, Syed reflects on her childhood home.

“We are staying here with faith in God,” she said. “We would leave immediately if only someone would take responsibility for developing the building. We are just waiting for this assurance.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA NEWS